The Pen is Mightier

The New Yorker:The Beauty of Slow Design

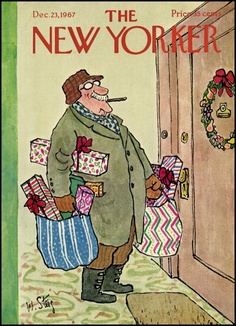

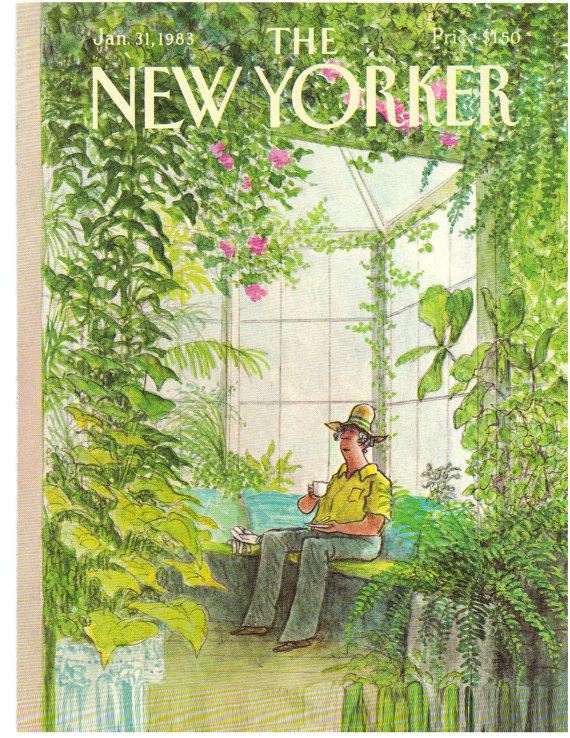

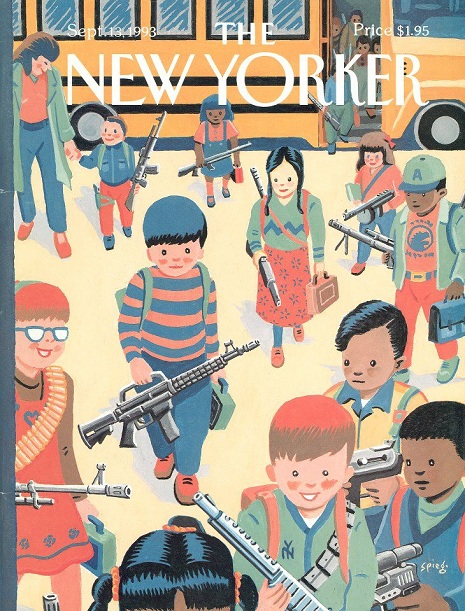

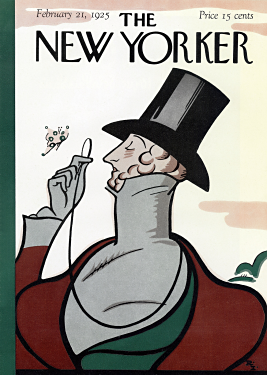

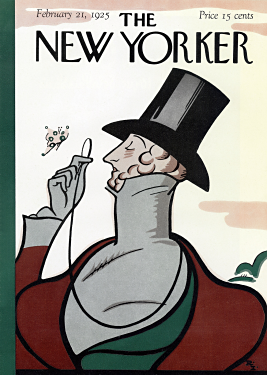

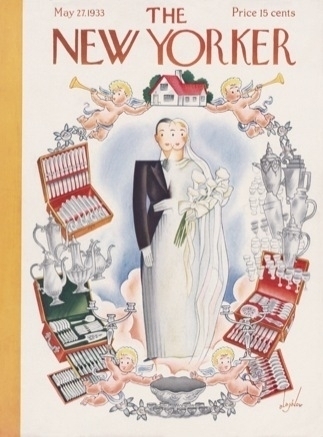

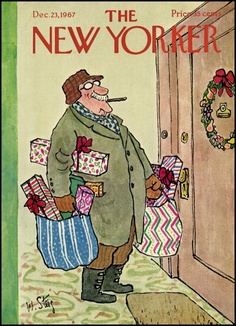

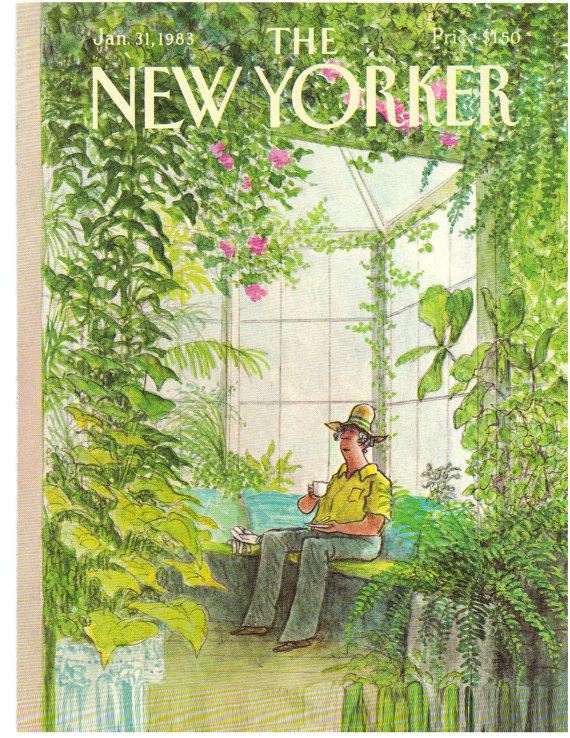

The New Yorker recently updated the design and interface for their mobile app and online blog as well as the printed version. Creating a fresh design for the mobile app and the blog seems inevitable due to the fast-growing mobile and social networking industries. However, the updated design of the print version is more like a digitized and modernized reconstruction of the classical design. Some people might criticize the design elements of The New Yorker for being boring; indeed, their design and format remained pretty much unchanged since the first issue was published in 1925. Yet, I appreciate their philosophy of slow design and timeless quality.

Personal Anecdote: Mr. Kang's

I was born in Seoul, Korea, but I do not have many memories of my hometown since I moved to China and spent most of my childhood there. Luckily, I could go back to Korea once every two or three years in the summer to visit my grandparents who are still in Seoul. And most of the images I perceived about my hometown were shaped whenever I went back to my grandparents' neighborhood. In my memory, the neighborhood was a very peaceful area: groups of children chatted and walked on the unpaved road, small red-bricked houses stood right next to each other, and my grandparents' home was at the end of a red-brick-walled alley.

The most memorable place in the neighborhood was an old and tiny family-owned corner shop called Mr. Kang's , which was not even the official name of the shop; no one from my family recalls the real name. I often went to that shop holding my grandma's hand and came back home licking a strawberry-flavored ice-cream. My mom told me that Mr. Kang's existed since she was a young girl; whenever I visited the shop with my mom, Mr. Kang would tell me funny stories that started with, “You know what, when your mom was your age…” Memories I have of the shop would make me feel nostalgic and warm my heart.

Whenever I visited my grandparents every two or three years, I noticed slight changes around the neighborhood: there were less children walking but more cars on the street. There were fewer small red-bricked houses but more tall buildings. Fortunately, my grandparents house and Mr. Kang's were still located at the opposite end of the red-brick-walled alley, unchanged.

I have not visited my grandparents for a while. The last time I visited Korea was the summer before I left China and moved to California in 2008. When I was in the cab looking at the window, I was shocked and overwhelmed by how much Seoul had changed: the groups of children walking had disappeared, instead more cars were parked on nicely paved roads and small red-bricked houses were transformed into gray and cold-looking skyscrapers. I was afraid that I would not be able to recognize my grandparents' home, and of course Mr. Kang's . The cab stopped at a familiar-looking entry of an alley. And I saw, among all the unfamiliar buildings and stores, the old tiny corner shop was still in the same spot. I was so glad and thankful. I finally felt comfortable and reassured among all these things that I had never seen around the neighborhood.

The Beauty of Slow Design

Innovative modifications and adaptations are absolutely necessary in the rapidly and frequently changing society, especially in the design fields. But I would like to raise a couple of questions: what is wrong with keeping a rarely changed design for a long time if the design itself is distinctive and noteworthy? Will the readers and the users who have built their long-term relationship with their favorite publications accept and appreciate the sudden changes?

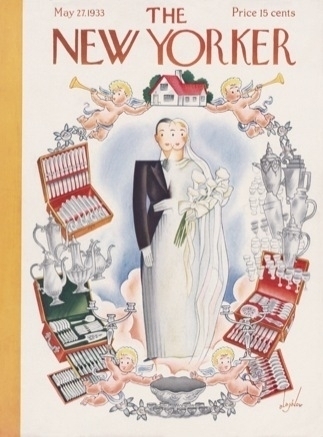

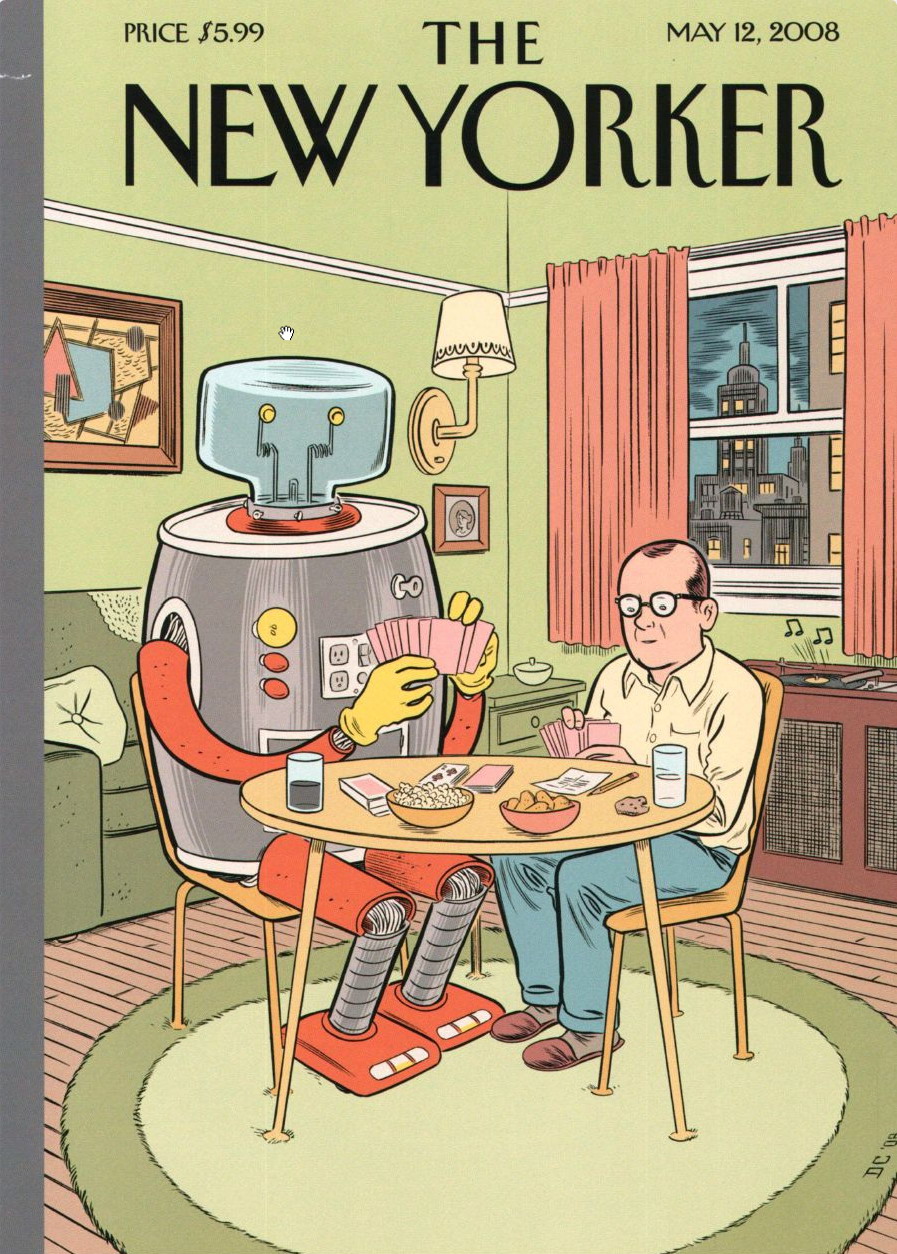

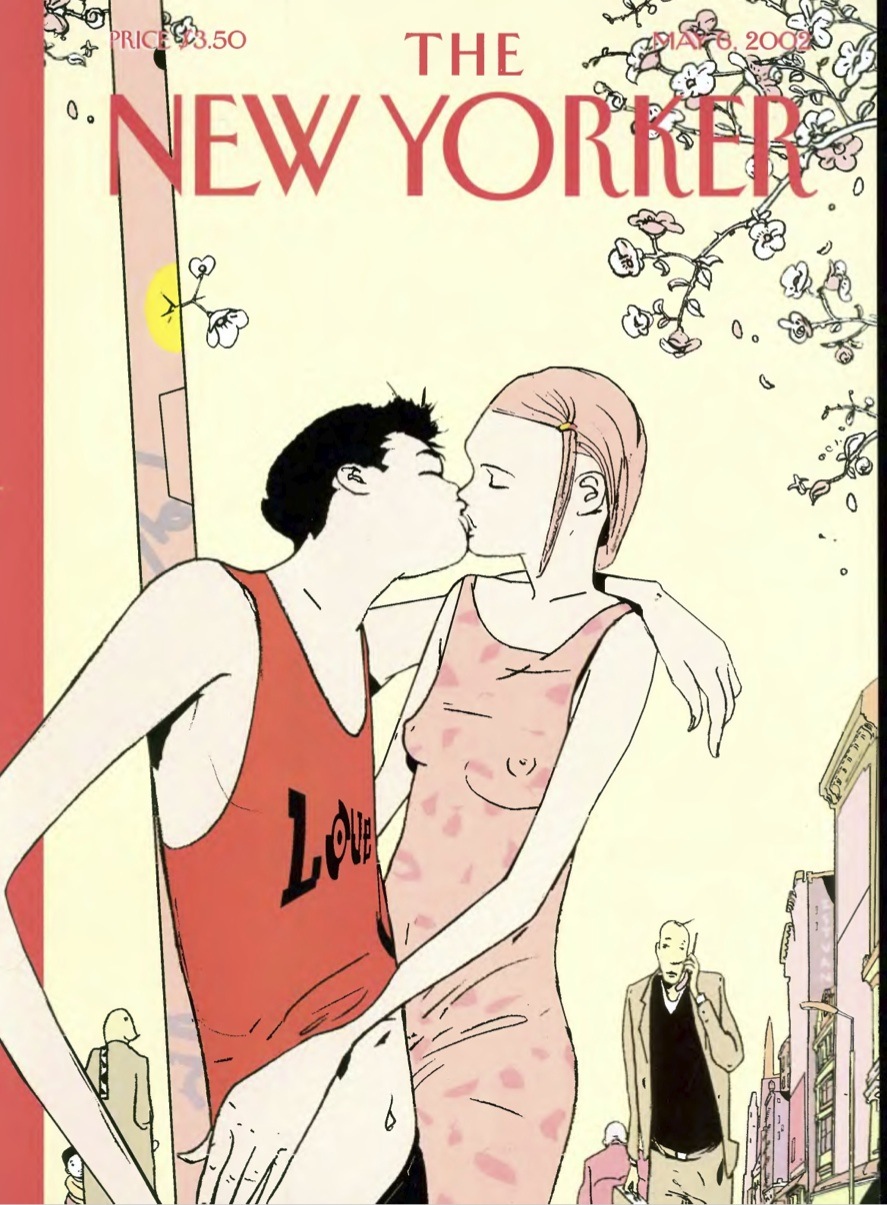

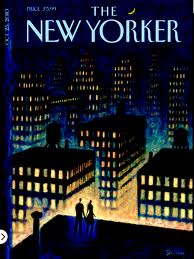

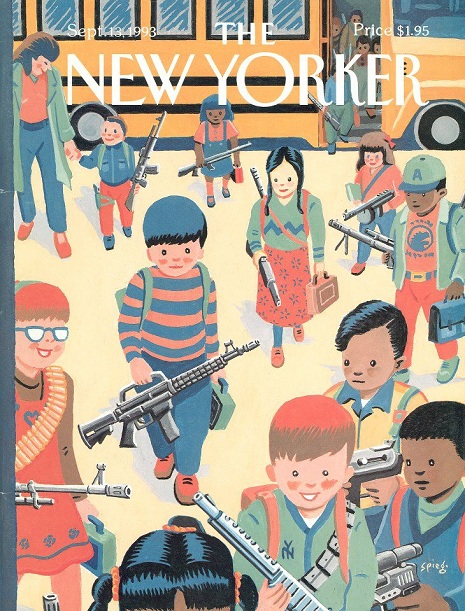

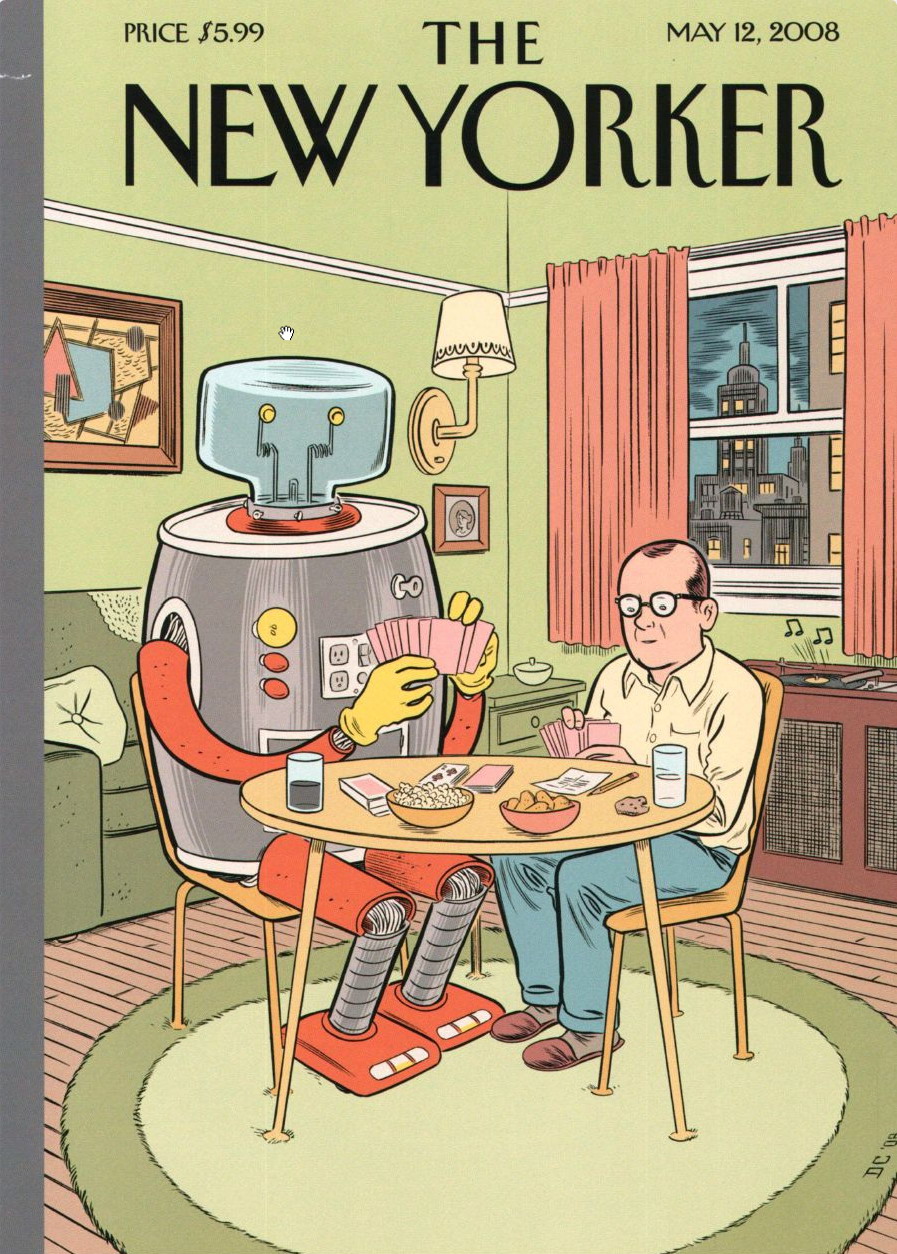

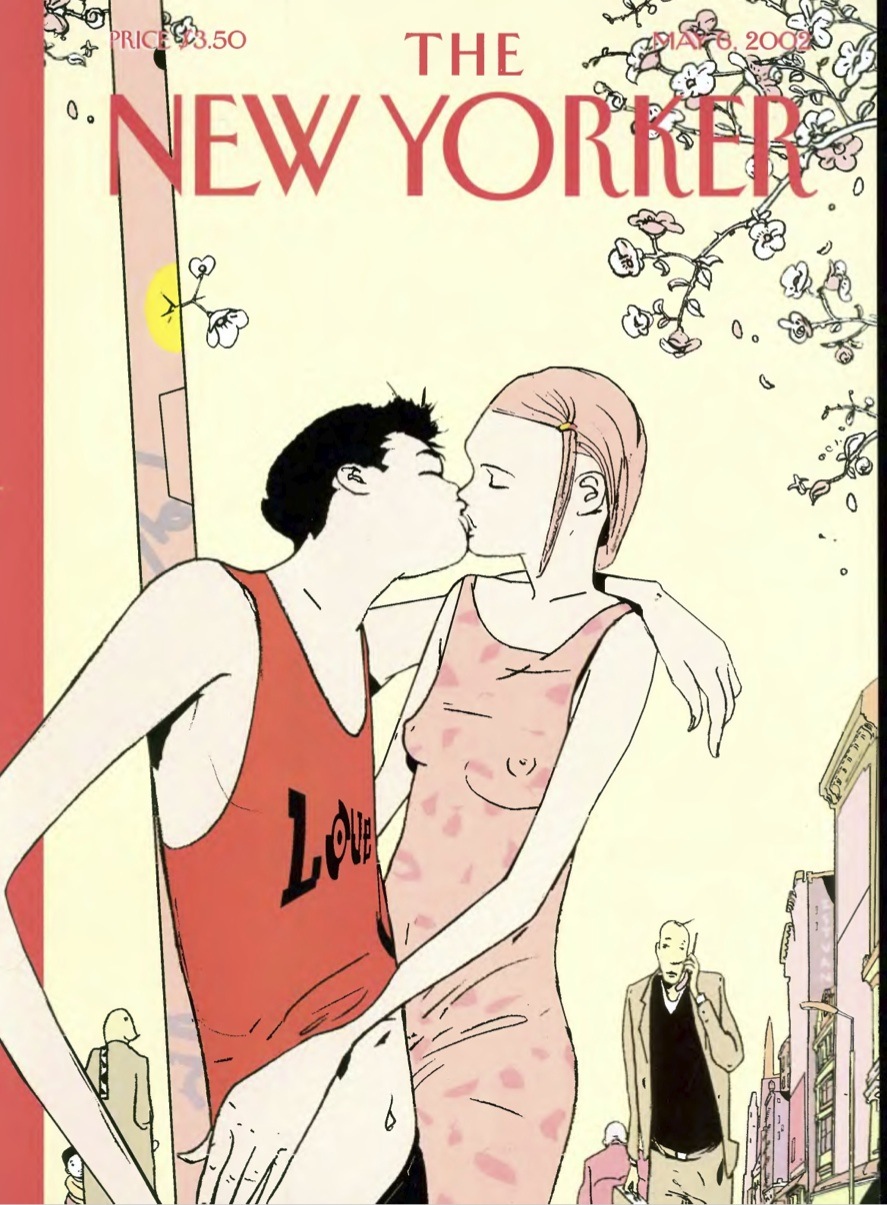

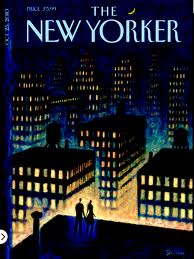

I believe that slowly developed and modified designs provoke sentiment and emotion; they are often associated with the user's nostalgia and the reminiscences from the past. The New Yorker's effort to reconstruct and modernize the design and editorial format based on their classical philosophy is a great example of the slow design movement. Since it was published in 1925, a countless number of long-term subscribers have spent their Mondays with printed copies of The New Yorker. They would recognize the distinctive and whimsical Irvin typeface of the headlines; they would create special scrapbooks or personal archives with their favorite cover designs, articles, editorials and comics; and they would conjure up specific recollections when they saw and made connections with the specific details of the publication. The New Yorker became a part of the readers' lives. They established a special relationship with each other over a long period of time in the same way that I am fond of my grandma's small neighborhood.

Now, imagine that the editors of The New Yorker decided to renovate every aspect of the publication: new typefaces, layouts, formats, even a different size and shape of the magazine. Will the readers, who have been adjusted to The New Yorker's slow design movement, celebrate and be easily accustomed to these changes? The unwarned renovation of The New Yorker is equivalent to the industrial development within my grandma's neighborhood. It is something that most people do not appreciate or even wanted in the first place. The unnecessary modifications of the design (even though it is hypothetical) might portray The New Yorker as a desperate and outdated magazine which attempting to get the public's attention in the rapidly shifting field of publication design. We should be aware that there is nothing wrong with a familiar and recognizable design. The New Yorker's original design from the first issue was sophisticated: it had simplicity and minimalistic characteristics within fancy and whimsical qualities, both functional and aesthetically pleasing. Thus reconstructing the classical design and layout with modern technology is a clever and effective approach to improve the design without diminishing the timeless quality.

*********************************************************************

Just like how the little corner shop in my grandma's neighborhood remains unchanged over time and greets me whenever I visit, The New Yorker's subtle changes will enhance their timeless and distinctive quality rather than forfeiting their reputation. The slow design movement is not a weakness. It is actually a strength that provides unique insight to the design among the fast-paced design industry.